By Joelle B

“Sexy, quiet. Shy, but down for a good time”. Lest you think I am describing myself, these are the opening lines of Janet Jackson’s ‘Damita Jo’. The track is introspective, self-reflective and confessional, strategically blending elements of hip-hop, pop and R&B (making it a quintessential product of 2004). With lyrics like “I do dance, I do music … I love doing my man’ and ‘Ms Janet don’t but Damita sho do’, it is clear the track serves a dual purpose: as the title track to Jackson’s 2004 album and to reveal a new side to Jackson’s idiosyncratic sex-positive persona.

This year marked the 20th anniversary of Janet Jackson’s eighth studio album Damita Jo. As described by Jackson, the album ‘is about love’ exploring all sides to a new relationship. Stacked with 22 tracks (unfortunately 8 of them are interludes), Damita Jo is steamy, sensual, and seductive — hallmarks of the music of Janet Jackson’s later career. In fact, Apple Music’s description of the album reinforces my assessment, describing the music as ‘so hot, it’s practically dripping in sweat.’

In my view, Damita Jo is a solid album, deserving a 6.8-7/10 on my personal scale. While it may not contain the best songs of Janet’s career, there are undeniable standouts like “R&B Junkie” (sampling Evelyn Champagne King’s “I’m in Love”) and “SloLove.” Both tracks effortlessly capture the essence of fun, blending 80s and Eurodisco influences, a sound very few artists—aside from perhaps Mariah Carey—were exploring in the 2000s. Upon release, however, the album received lukewarm reviews, with some (male) observers taking a critical approach, describing the album as reeking of ‘desperation’. For me, while it may not have the timeless quality of The Velvet Rope or be as era-defining as All For You, Damita Jo remains as a time capsule for the early 2000s sound.

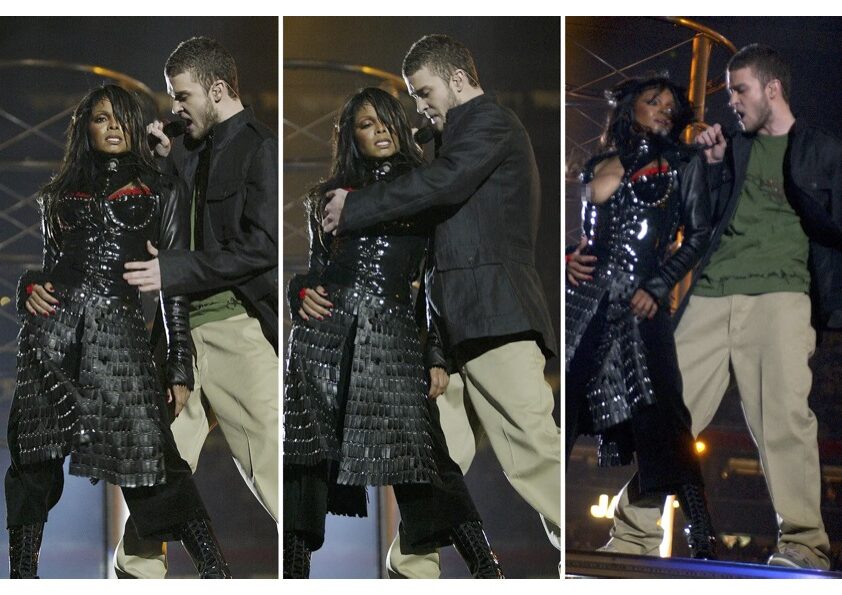

The legacy of Damita Jo is often intertwined with the infamous halftime show performance in which Justin Timberlake, as so eloquently described by Digital Spy in 2004, “yanked off a leather patch covering Jackson’s right breast,” exposing it to 140 million viewers. This brief moment, dramatically shifted the perception of Damita Jo. The halftime show, which also featured now largely forgotten cameos from Nelly and Diddy performing “Hot in Herre”— the lyrics of which, in retrospect, seem like an unfortunate foreshadowing, completely overshadowed the album. Damita Jo, my fellow Taurean, was immediately misunderstood. To me, both the album and the persona, represented an extension of Janet’s vision, emphasising that “sex isn’t just fire and heat, it’s natural beauty,” as she explained in a 1993 Rolling Stone interview. However, it was unfairly dismissed as a hypersexualized attempt to stay relevant in a youth-driven music landscape, with some critics calling it “not just tired, but embarrassing”—a categorically wrong interpretation (forgive my hyperbole).

If you’re familiar with Janet Jackson’s discography, you know she has long been a pioneer of sexual liberation, emphasising pleasure and healthy communication. Her music often conveys intimacy through subtle, nuanced elements of vocal style and production. However, the controversy around her Super Bowl Halftime show seems to stem from the fact that it presented a direct and undeniable image of her sexuality—one that starkly contrasted with the more implied sensuality found in her music, such as in songs like “Would You Mind” and “Rope Burn.”

It’s widely understood that conversations surrounding female sexuality are often met with gendered double standards and excessive slut-shaming. However, when discussing the treatment of Damita Jo (both the album and persona) it’s important to recognize the harsher judgement cast on Black women’s sexuality by dominant white culture. Whether due to the legacy of colonialism or white patriarchal rule, Black women’s bodies have long been seen as threats to “stable white order.” This isn’t a new or radical idea—the Combahee River Collective Statement from 1977 pointed out that Black women have always, even just by their physical presence, ’an adversary stance to white male rule’ – ie their very existence can be seen as a rejection of, or resistance to, the norms of white patriarchy, which has always sought to control or oppress black bodies.

The very canvas of a black woman’s body has long been associated with ideas of irresponsibility and promiscuity. Again, this isn’t a new idea. As Peter Bardaglio noted in his discussion of the treatment of African American slaves, it was commonly believed that “their intercourse is promiscuous and regulated by their owners.” When applied to the treatment of Damita Jo, the notion of regulation—or more bluntly, punishment—becomes evident in her blacklisting from radio following the Super Bowl incident, which severely impacted the album’s sales. Additional acts of punishment, as outlined in a USA today article, included her removal from a Grammy Awards tribute to Luther Vandross, and the removal of the statue Mickey Mouse dressed in her Rhythm Nation outfit.

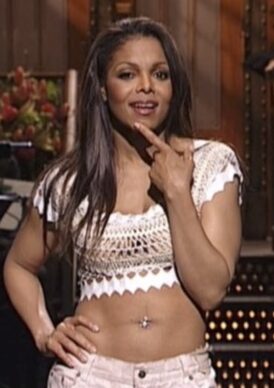

An NPR article from the same year highlights a stark contrast in the treatment of Black and white bodies in mainstream media. Discussing the “shifting erogenous zones” of 2004, Harold Koda praised the “Britney Spears effect,” saying, “She projects a wholesome, accessible image… She is so all-American that a bare midriff or piercing on that canvas becomes acceptable to a broader audience.” While I do love me some Britney, and I don’t intend to imply that she was not mistreated by the media, it’s telling what makes her “all-American” and inspires young Americans to showcase “their best feature” compared to Janet Jackson.

Broader discussions about how we retroactively view the treatment of Damita Jo can be seen in the media language surrounding the incident and the roles of both Janet Jackson and Justin Timberlake. Timberlake was strategically absolved of blame, remaining unapologetic—despite his action being the cause of the controversy. In fact, he appeared characteristically smug, at one point implying the stunt was planned, saying, “We love giving you something to talk about,” effectively distancing himself from the fallout. Janet, on the other hand, was repeatedly forced to address her role, casting an unfortunate shadow over both the Damita Jo album and persona.

]With all of this in mind, it only adds to the reasons why Damita Jo deserves a complete reevaluation. Sure, I could go on about the strategic choices made for the album – incorporating Kanye as a producer should have been rewarded commercially. But I won’t bore you with that. Thankfully, it seems that the tide is finally turning, and Damita Jo is starting to get the recognition it deserves. If there’s one thing the album teaches us is the age old lesson of ignoring media-induced moral panics. While Janet is by no means defined by the incident, as evidenced by her current successful Together Again tour (which is coming to the UK in October!) I encourage you to listen to Damita Jo. Not out of pity, but because there’s genuinely good music on there.

Best Tracks from the Album

- I Want You – produced by Kanye West, the track has a ‘doowoppy’ feel (Janets words not mine) and makes the idea of pining for someone almost appealing.

And, as i previously, mentioned RnB Junkie and SloLove

All Nite (Don’t Stop) – (which was co-produced by Murlyn Music Group – who also worked on Britney Spears Toxic) a song I’m convinced would have been a hit.

Leave a Reply